Douglas Blumeyer's RTT How-To

(to be broken out to pages named "Douglas Blumeyer's RTT How-To")

This is the reference I wish I had when I was learning RTT, or Regular Temperament Theory. There are other great resources out there, but this is how I would have liked to have learned it myself. I might say these materials lean more visual and geometric than others I've seen, and focus on elementary computation and representation rather than theory. It's not really a big picture introduction, it doesn't explore musical applications, and its algorithms are for humans, not computers. In any case, I hope others are able to benefit from these tools and explanations.

intro

What’s tempering, you ask, and why temper? I won’t be answering those questions in depth here. Plenty has been said about the “what” and “why” elsewhere[1]. These materials are about the “how”.

But I will at least give brief answers. In the most typical case, tempering means adjusting the tuning of the primes — the harmonic building blocks of your music — only a little bit, so that you can still sense what chords and melodies are “supposed” to be, but in just such a way that the interval math “adds up” in more practical ways than it does in pure just intonation (JI). This is also what equal divisions (EDs) do, but where EDs go “all the way”, compromising more JI accuracy for more ease of use, RTT finds a “middle path”: minimizing the accuracies you sacrifice, while maximizing ease of use. Understanding that much of the “what”, you can refer to this table to see basically “why”:

| ED | RTT (middle path) | JI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ease of use | ★★★★ | ★★★ | ★ |

| harmonic accuracy | ★ | ★★★ | ★★★★ |

The point is that a tempered tuning manages to score high for both usability and harmonic accuracy, and therefore the case can be made that it is better overall than either a straight ED or straight JI. On this table (which reflects my opinion), RTT got six total stars while ED and JI each only got five. (And this doesn't even account for the power RTT has to create fascinating new harmonic effects, like comma pumps and essentially tempered chords, which EDs can do to a lesser extent.)

But, you protest: this tutorial is pretty long, and it contains a bunch of gnarly diagrams and advanced math concepts, so how could RTT possibly be easier to use than JI? Well, what I’ve rated above is the ease of use after you’ve chosen your particular ED, RTT, or JI tuning. It’s the ease of writing, reading, reasoning about, communicating about, teaching, performing, listening to, and analyzing the music in said tuning. This is different from how simple it is to determine a desirable tuning up front.

Determining desirable tunings is a whole other beast. Perhaps contrary to popular belief, xenharmonic musicians — composers and performers alike — can mostly insulate themselves from this stuff if they like. It’s fine to nab a popular and well-reviewed tuning off the shelf, without deeply understanding how or why it’s there, and just pump, jam, or riff away. There's a good chance you could naturally pick up what's cool about a tuning without ever learning the definition of "temper out" or "generator". But if you do want to be deliberate about it, to mod something, rifle through the obscure section, or even discover your own tuning, then you must prepare to delve deeper into the xenharmonic fold. That’s why this resource is here, for RTT.

As for whether determining a middle path tuning is any harder than determining an ED or JI tuning, I think it would be fair to say that in the exact same way that a middle path tuning — once attained — combines the strengths of ED and of JI, determining a middle path tuning combines the challenges of determining good ED tunings and of determining good JI tunings. You have been warned.

maps

In this first section, you will learn about maps — one of the basic building blocks of temperaments — and the effect maps have on musical intervals.

vectors and covectors

It’s hard to get too far with RTT before you understand vectors and covectors, so let’s start there.

Until stated otherwise, this material will assume the 5 prime-limit.

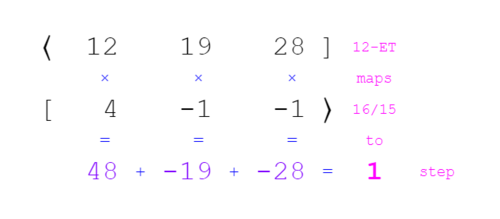

If you’ve previously worked with JI, you may already be familiar with vectors. Vectors are a compact way to express JI intervals in terms of their prime factorization, or in other words, their harmonic building blocks. In JI, and in most contexts in RTT, vectors simply list the count of each prime, in order. For example, 16/15 is [4 -1 -1⟩ because it has four 2’s in its numerator, one 3 in its denominator, and also one 5 in its denominator. You can look at each term as an exponent: 2⁴ × 3⁻¹ × 5⁻¹ = 16/15.

And if you’ve previously worked with EDOs, you may already be familiar with covectors. Covectors are a compact way to express EDOs in terms of the count of its steps it takes to reach its approximation of each prime harmonic, in order. For example, 12-EDO is ⟨12 19 28]. The first term is the same as the name of the EDO, because the first prime harmonic is 2/1, or in other words: the octave. So this covector tells us that it takes 12 steps to reach 2/1 (the octave), 19 steps to reach 3/1 (the tritave), and 28 steps to each 5/1 (the pentave). Any or all of those intervals may be approximate.

If the musical structure that the mathematical structure called a vector represents is an interval, the musical structure that the mathematical structure called a covector represents is called a map.

Note the different direction of the brackets between covectors and vectors: covectors ⟨] point left, vectors [⟩ point right.

Covectors and vectors give us a way to bridge JI and EDOs. If the vector gives us a list of primes in a JI interval, and the covector tells us how many steps it takes to reach the approximation of each of those primes individually in an EDO, then when we put them together, we can see what step of the EDO should give the closest approximation of that JI interval. We say that the JI interval maps to that number of steps in the EDO. Calculating this looks like ⟨12 19 28][4 -1 -1⟩, and all that means is to multiply matching terms and sum the results (this is called the dot product).

So, 16/15 maps to one step in 12-EDO (see Figure 2a).

For another example, can quickly find the fifth size for 12-EDO from its map, because 3/2 is [-1 1 0⟩, and so ⟨12 19 28][-1 1 0⟩ = (12 × -1) + (19 × 1) = 7. Similarly, the major third — 5/4, or [-2 0 1⟩ — is simply 28 - 12 - 12 = 4.

WolframAlpha's syntax is slightly different than what we use in RTT, but it's pretty alright for a free online tool capable of handling most of the math we need to do in RTT, so we're going to be supplementing several topics with WolframAlpha examples as we go. Here's the first:

| input | output |

|---|---|

{12,19,28}.{-1,1,0}

|

7 |

tempering out commas

Here’s where things start to get really interesting.

We can also see that the JI interval 81/80 maps to zero steps in 12-EDO, because ⟨12 19 28][-4 4 -1⟩ = 0; we therefore say this JI interval vanishes in 12-EDO, or that it is tempered out. This type of JI interval is called a comma, and this particular one is called the meantone comma.

The immediate conclusion is that 12-EDO is not equipped to approximate the meantone comma directly as a melodic or harmonic interval, and this shouldn’t be surprising because 81/80 is only around 20¢, while the (smallest) step in 12-EDO is five times that.

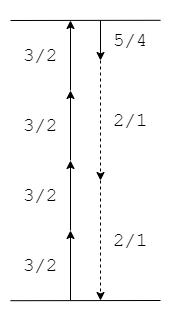

But a more interesting way to think about this result involves treating [-4 4 -1⟩ not as a single interval, but as the end result of moving by a combination of intervals. For example, moving up four fifths, 4 × [-1 1 0⟩ = [-4 4 0⟩, and then moving down one pentave [0 0 -1⟩, gets you right back where you started in 12-EDO. Or, in other words, moving by one pentave is the same thing as moving by four fifths (see Figure 2b). One can make compelling music that exploits such harmonic mechanisms.

From this perspective, the disappearance of 81/80 is not a shortcoming, but a fascinating feature of 12-EDO; we say that 12-EDO supports the meantone temperament. And 81/80 in 12-EDO is only the beginning of that journey. For many people, tempering commas is one of the biggest draws to RTT.

But we’re still only talking about JI and EDOs. If you’re familiar with meantone as a historical temperament, you may be aware already that it is neither JI nor an EDO. Well, we’ve got a ways to go yet before we get there.

One thing we can easily begin to do now, though, is this: refer to EDOs instead as ETs, or equal temperaments. The two terms are roughly synonymous, but have different implications and connotations. To put it briefly, the difference can be found in the names: 12 Equal Divisions of the Octave suggests only that your goal is equally dividing the octave, while 12 Equal Temperament suggests that your goal is to temper and that you have settled on a single equal step to accomplish that. Because we’re learning about temperament theory here, it would be more appropriate and accurate to use the local terminology. 12-ET it is, then.

approximating JI

If you’ve seen one map before, it’s probably ⟨12 19 28]. That’s because this map is the foundation of conventional Western tuning: 12 equal temperament. A major reason it stuck is because — for its low complexity — it can closely approximate all three of the 5 prime-limit harmonics 2, 3, and 5 at the same time.

One way to think of this is that 12:19:28 is an excellent low integer approximation of log(2:3:5). That's a really compact way of saying that each of these sets of three numbers has the same ratio between each pair of them:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{19}{12} = 1.583 ≈ \frac{log(3)}{log(2)} = 1.585 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{28}{12} = 2.333 ≈ \frac{log(5)}{log(2)} = 2.322 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{28}{19} = 1.474 ≈ \frac{log(5)}{log(3)} = 1.465 }[/math]

You may be more familiar with seeing the base specified for a logarithm, but in this case the base is irrelevant as long as you use the same base for both numbers. If you don't see why, try experimenting with different bases and see that the ratio comes out the same[2].

But why take the logarithm at all? Because a) 2, 3, and 5 are not exponents, b) 12, 19, and 28 are exponents, and c) logarithms give exponents.

- 2, 3, and 5 are not exponents. They’re multipliers. To be specific, they’re multipliers of frequency. If the root pitch 1(/1) is 440Hz, then 2(/1) is 880Hz, 3(/1) is 1320Hz, and 5(/1) is 2200Hz.

- 12, 19, and 28 are exponents. Think of it this way: the map tells us to find some shared number g, called a generator, such that g¹² ≈ 2, g¹⁹ ≈ 3, and g²⁸ ≈ 5. It doesn’t tell us whether all of those approximations can be good at the same time, but it tells us that’s what we’re aiming for. For this map, it happens to be the case that a generator of around 1.059 will be best. Note that this generator is the same thing as one step of our ET. Also note that by thinking this way, we are thinking in terms of frequency (e.g. in Hz), not pitch (e.g. in cents): when we move repeatedly in pitch, we repeatedly add, which can be expressed as multiplication, e.g. 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ + 100¢ = 12×100¢ = 1200¢, while when we move repeatedly in frequency, we repeatedly multiply, which can be expressed as exponentiation, e.g. 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 = 1.059¹² ≈ 2. We can therefore say that frequency and pitch are two realms separated by one logarithmic order.

- logarithms give exponents. A logarithm answers the question, “What exponent do I raise this base to in order to get this value?” So when I say 12 = logg2 I’m saying there’s some base g which to the twelfth power gives 2, and when I say 19 = logg3 I’m saying there’s some base g which to the nineteenth power gives 3, etc. (That’s how I found 1.059, by the way; if g¹² ≈ 2, and I take the twelfth root of both sides, I get g = ¹²√2 ≈ 1.05946, and I could have just easily taken ¹⁹√3 ≈ 1.05952 or ²⁸√5 ≈ 1.05916).

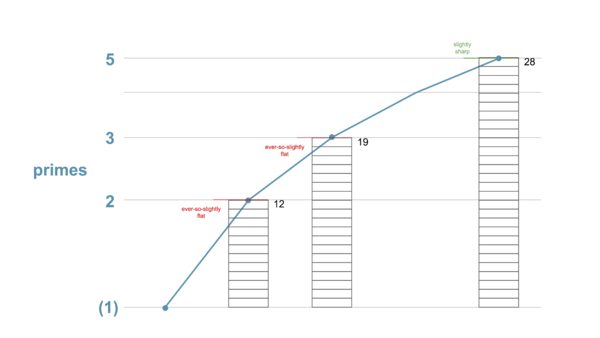

So when I say 12:19:28 ≈ log(2:3:5) what I’m saying is that there is indeed some shared generator g for which logg2 ≈ 12, logg3 ≈ 19, and logg5 ≈ 28 are all good approximations all at the same time, or, equivalently, a shared generator g for which g¹² ≈ 2, g¹⁹ ≈ 3, and g²⁸ ≈ 5 are all good approximations at the same time (see Figure 2c). And that’s a pretty cool thing to find! To be clear, with g = 1.059, we get g¹² ≈ 1.9982, g¹⁹ ≈ 2.9923, and g²⁸ ≈ 5.0291.

Another glowing example is the map ⟨53 84 123], for which a good generator will give you g⁵³ ≈ 2.0002, g⁸⁴ ≈ 3.0005, g¹²³ ≈ 4.9974. This speaks to historical attention given to 53-ET. So while 53:84:123 is an even better approximation of log(2:3:5) (and you won’t find a better one until 118:187:274), of course its integers aren’t as low, so that lessens its appeal.

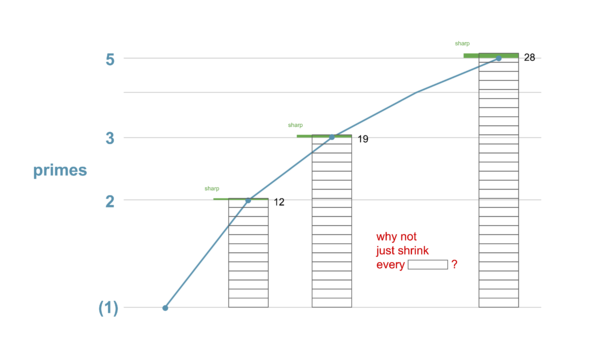

Why is this rare? Well, it’s like a game of trying to get these numbers to line up (see Figure 2d):

If the distance between entries in the row for 2 are defined as 1 unit apart, then the distance between entries in the row for prime 3 are 1/log₂3 units apart, and 1/log₂5 units apart for the prime 5. So, near-linings up don’t happen all that often![3] (By the way, any vertical line drawn through a chart like this is what we'll be calling here a uniform map; elsewhere you may find this called a “generalized patent val”.[4])

And why is this cool? Well, if ⟨12 19 28] approximates the harmonic building blocks well individually, then JI intervals built out of them, like 16/15, 5/4, 10/9, etc. should also be reasonably closely approximated overall, and thus recognizable as their JI counterparts in musical context. You could think of it like taking all the primes in a prime factorization and swapping in their approximations. For example, if 16/15 = 2⁴ × 3⁻¹ × 5⁻¹ ≈ 1.067, and ⟨12 19 28] approximates 2, 3, and 5 by 1.059¹² ≈ 1.998, 1.059¹⁹ ≈ 2.992, and 1.059²⁸ ≈ 5.029, respectively, then ⟨12 19 28] maps 16/15 to 1.998⁴ × 2.992⁻¹ × 5.029⁻¹ ≈ 1.059, which is indeed pretty close to 1.067. Of course, we should also note that 1.059 is the same as our step of ⟨12 19 28], which checks out with our calculation we made in the previous section that the best approximation of 16/15 in ⟨12 19 28] would be 1 step.

tuning & pure octaves

Now, because the octave is the interval of equivalence in terms of human pitch perception, it’s a major convenience to enforce pure octaves, and so many people prefer the first term to be exact. In fact, I’ll bet many readers have never even heard of or imagined impure octaves, if my own anecdotal experience is any indicator; the idea that I could temper octaves to optimize tunings came rather late to me.

Well, you’ll notice that in the previous section, we did approximate the octave, using 1.998 instead of 2. But another thing ⟨12 19 28] has going for it is that it excels at approximating 5-limit JI even if we constrain ourselves to pure octaves, locking g¹² to exactly 2: (¹²√2)¹⁹ ≈ 2.997 and (¹²√2)²⁸ ≈ 5.040. You can see that actually the approximation of 3 is even better here, marginally; it’s the error on 5 which is lamentable.

When we don’t enforce pure octaves, tuning becomes a more interesting problem. Approximating all three primes at once with the same generator is a balancing act. At least one of the primes will be tuned a bit sharp while at least one of them will be tuned a bit flat. In the case of ⟨12 19 28], the 5 is a bit sharp, and the 2 and 3 are each a tiny bit flat (as you can see in Figure 2c).

If you think about it, you would never want to tune all the primes sharp at the same time, or all of them flat; if you care about this particular proportion of their tunings, why wouldn’t you shift them all in the same direction, toward accuracy, while maintaining that proportion? (see Figure 2e)

This matter of choosing the exact generator for a map is called tuning, and if you’ll believe it, we won’t actually talk about that in detail again until much later. Temperament — the second ‘T’ in “RTT” — is the discipline concerned with choosing an interesting map, and tuning can remain largely independent from it. The temperament is only concerned with the fact that — no matter what exact size you ultimately make the generator — it is the case e.g. that 12 of them make a 2, 19 of them make a 3, and 28 of them make a 5. So, for now, whenever we show a value for g, assume we’ve given a computer a formula for optimizing the tuning to approximate all three primes equally well. As for us humans, let’s stay focused on tempering.

a multitude of maps

Suppose we want to experiment with ⟨12 19 28]’s map a bit. We’ll change one of the terms by 1, so now we have ⟨12 20 28]. Because the previous map did such a great job of approximating the 5-limit (i.e. log(2:3:5)), though, it should be unsurprising that this new map cannot achieve that feat. The proportions, 12:20:28, should now be about as out of whack as they can get. The best generator we can do here is about 1.0583 (getting a little more precise now), and 1.0583¹² ≈ 1.9738 which isn’t so bad, but 1.0583¹⁹ = 3.1058 and 1.0583²⁸ = 4.8870 which are both way off! And they’re way off in the opposite direction — 3.1058 is too big and 4.8870 is too small — which is why our tuning formula for g, which is designed to make the approximation good for every prime at once, can’t improve the situation: either sharpening or flattening helps one but hurts the other.

The results of such inaccurate approximation are a bit chaotic. A ratio like 16/15 — where the factors of 3 and 5 are on the same side of the fraction bar and therefore cancel out each other’s error — fares relatively alright, if by “alright” we mean it gets tempered out despite being about 112¢ in JI. On the other hand, an interval like 27/25 where the factors of 3 and 5 are on opposite sides of the fraction bar and thus their errors compound, gets mapped to a whopping 4 steps, despite only being about 133¢ in JI.

If your goal is to evoke JI-like harmony, then, ⟨12 20 28] is not your friend. Feel free to work out some other variations on ⟨12 19 28] if you like, such as ⟨12 19 29] maybe, but I guarantee you won’t find a better one that starts with 12 than ⟨12 19 28].

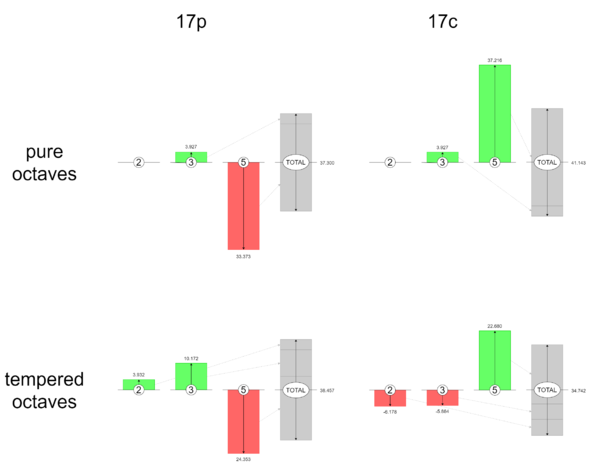

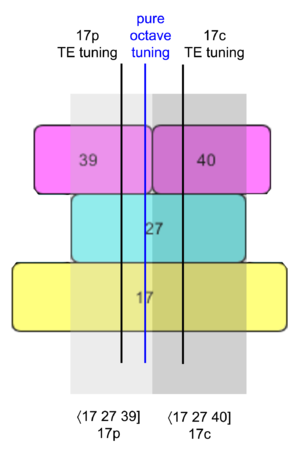

So the case is cut-and-dry for ⟨12 19 28], and therefore from now on I'm simply going to refer to this ET by "12-ET" rather than spelling out its map. But other ETs find themselves in trickier situations. Consider 17-ET. One option we have is the map ⟨17 27 39], with a generator of about 1.0418, and prime approximations of 2.0045, 3.0177, 4.9302. But we have a second reasonable option here, too, where ⟨17 27 40] gives us a generator of 1.0414, and prime approximations of 1.9929, 2.9898, and 5.0659. In either case, the approximations of 2 and 3 are close, but the approximation of 5 is way off. For ⟨17 27 39], it’s way small, while for ⟨17 27 40] it’s way big. The conundrum could be described like this: any generator we could find that divides 2 into about 17 equal steps can do a good job dividing 3 into about 27 equal steps, too, but it will not do a good job of dividing 5 into equal steps; 5 is going to land, unfortunately, right about in the middle between the 39th and 40th steps, as far as possible from either of these two nearest approximations. To do a good job approximating prime 5, we’d really just want to subdivide each of these steps in half, or in other words, we’d want 34-ET.

Curiously, ⟨17 27 39] is the map for which each prime individually is as closely approximated as possible when prime 2 is exact, so it is in a sense the naively best map for 17-ET, however, if that constraint is lifted, and we’re allowed to either temper prime 2 and/or choose the next-closest approximations for prime 5, the overall approximation can be improved; in other words, even though 39 steps can take you just a tiny bit closer to prime 5 than 40 steps can, the tiny amount by which it is closer is less than the improvements to the tuning of primes 2 and 3 you can get by using ⟨17 27 40]. So again, the choice is not always cut-and-dry; there’s still a lot of personal preference going on in the tempering process.

So some musicians may conclude “17-ET is clearly not cut out for 5-limit music,” and move on to another ET. Other musicians may snicker maniacally, and choose one or the other map, and begin exploiting the profound and unusual 5-limit harmonic mechanisms it affords. ⟨17 27 40], like ⟨12 19 28], tempers out the meantone comma [-4 4 -1⟩, so even though fifths and major thirds are different sizes in these two ETs, the relationship that four fifths equals one major third is shared. ⟨17 27 39], on the other hand, does not work like that, but what it does do is temper out 25/24, [-3 -1 2⟩, or in other words, it equates one fifth with two major thirds.

If you’re enforcing pure octaves, the difference between ⟨17 27 39] and ⟨17 27 40] is nominal, or contextual. The steps in either case are identical: exactly ¹⁷√2, or 1200/17=70.588¢. You simply choose to think of 5 as being approximated by either 39 or 40 of those steps, or imply it in your composition. But when octaves are freed to temper, then the difference between these two maps becomes pronounced. When optimizing for ⟨17 27 39], the best step size is 70.225¢, but when optimizing for ⟨17 27 40], the best step size is more like 70.820¢.

You will sometimes see maps like 17-ET’s distinguished from each other using names like 17p and 17c. This is called wart notation.

At this point you should have a pretty good sense for why choosing a map makes an important impact on how your music sounds. Now we just need to help you find and compare maps! Or, similarly, how to find and compare intervals to temper. To do this, we need to give you the ability to navigate tuning space.

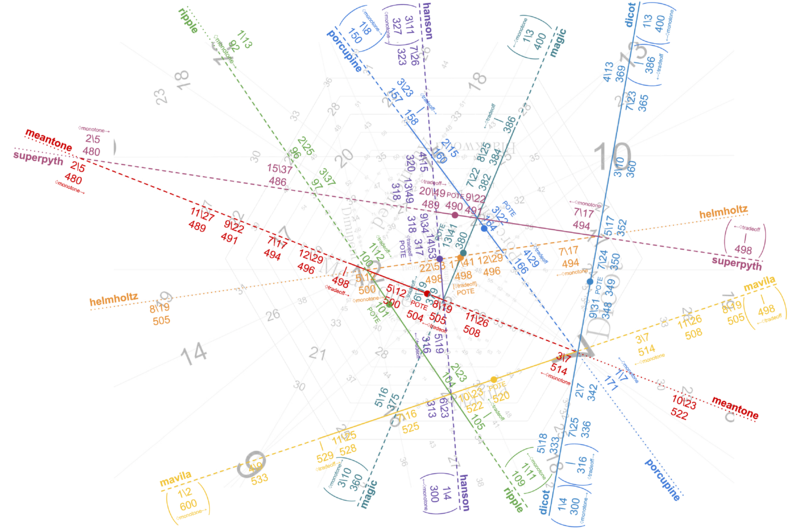

projective tuning space

In this section, we will be going into potentially excruciating detail about how to read the projective tuning space diagram featured prominently in Paul Erlich's Middle Path paper. For me personally, attaining total understanding of this diagram was critical before the linear algebra stuff (that we'll discuss afterwards) started to mean much to me. But other people might not work that way, and the extent of detail I go into in this section is not necessary to become competent with RTT (in fact, to my delight, one of the points I make in this section was news to Paul himself). So if you're already confident about reading the PTS diagram, you may try skipping ahead.

intro to PTS

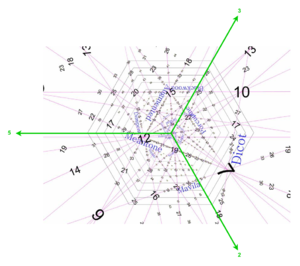

This is 5-limit projective tuning space, or PTS for short (see Figure 3a). This diagram was created by RTT pioneer Paul Erlich. It compresses a huge amount of valuable information into a small space. If at first it looks overwhelming or insane, do not despair. It may not be instantly easy to understand, but once you learn the tricks for navigating it from these materials, you will find it is very powerful. Perhaps you will even find patterns in it which others haven’t found yet.

I suggest you open this diagram in another window and keep it open as you proceed through these next few sections, as we will be referring to it frequently.

If you’ve worked with 5-limit JI before, you’re probably aware that it is three-dimensional. You’ve probably reasoned about it as a 3D lattice, where one axis is for the factors of prime 2, one axis is for the factors of prime 3, and one axis is for the factors of prime 5. This way, you can use vectors, such as [-4 4 -1⟩ or [1 -2 1⟩, just like coordinates.

PTS can be thought of as a projection of 5-limit JI map space, which similarly has one axis each for 2, 3, and 5. But it is no JI pitch lattice. In fact, in a sense, it is the opposite! This is because the coordinates in map space aren’t prime count lists, but maps, such as ⟨12 19 28]. That particular map is seen here as the biggish, slightly tilted numeral 12 just to the left of the center point.

And the two 17-ETs we looked at can be found here too. ⟨17 27 40] is the slightly smaller numeral 17 found on the line labeled “meantone” which the 12 is also on, thus representing the fact we mentioned earlier that they both temper it out. The other 17, ⟨17 27 39], is found on the other side of the center point, aligned horizontally with the first 17. So you could say that map space plots ETs, showing how they are related to each other.

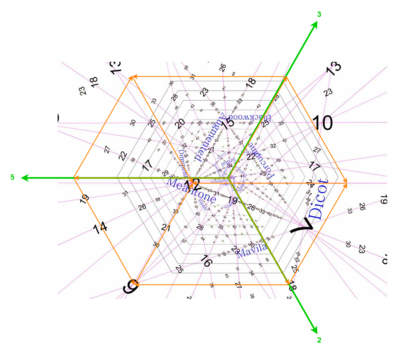

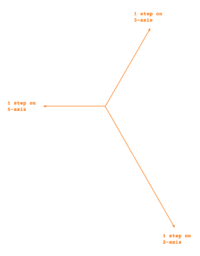

Of course, PTS looks nothing like this JI lattice (see Figure 3b). This diagram has a ton more information, and as such, Paul needed to get creative about how to structure it. It’s a little tricky, but we’ll get there. For starters, the axes are not actually shown on the PTS diagram; if they were, they would look like this (see Figure 3c).

The 2-axis points toward the bottom right, the 3-axis toward the top right, and the 5-axis toward the left. These are the positive halves of each of these axes; we don’t need to worry about the negative halves of any of them, because every term of every ET map is positive.

And so it makes sense that ⟨17 27 40] and ⟨17 27 39] are aligned horizontally, because the only difference between their maps is in the 5-term, and the 5-axis is horizontal.

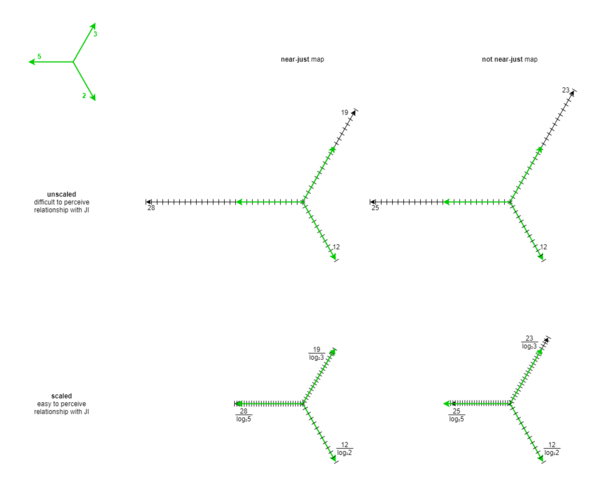

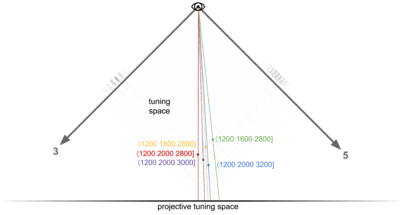

scaled axes

You might guess that to arrive at that tilted numeral 12, you would start at the origin in the center, move 12 steps toward the bottom right (along the 2-axis), 19 steps toward the top right (not along, but parallel to the 3-axis), and then 28 steps toward the left (parallel to the 5-axis). And if you guessed this, you’d probably also figure that you could perform these moves in any order, because you’d arrive at the same ending position regardless (see Figure 3d).

If you did guess this, you are on the right track, but the full truth is a bit more complicated than that.

The first difference to understand is that each axis’s steps have been scaled proportionally according to their prime (see Figure 3e). To illustrate this, let’s highlight an example ET and compare its position with the positions of three other ETs:

- the one which is one step away from it on the 5-axis,

- the one which is one step away from it on the 3-axis, and

- the one which is one step away from it on the 2-axis.

Our example ET will be 40. We'll start out at the map ⟨40 63 93]. This map is a default of sorts for 40-ET, because it’s the map where all three terms are as close as possible to JI when prime 2 is exact (we'll be calling it a simple map here, though elsewhere you may find it called a "patent val"[5]).

From here, let’s move by a single step on the 5-axis by adding 1 to the 5-term of our map, from 93 to 94, therefore moving to the map ⟨40 63 94]. This map is found directly to the left. This makes sense because the orientation of the 5-axis is horizontal, and the positive direction points out from the origin toward the left, so increases to the 5-term move us in that direction.

Back from our starting point, let’s move by a single step again, but this time on the 3-axis, by adding 1 to the 3-term of our map, from 63 to 64, therefore moving to the map ⟨40 64 93]. This map is found up and to the right. Again, this direction makes sense, because it’s the direction the 3-axis points.

Finally, let’s move by a single step on the 2-axis, from 40 to 41, moving to the map ⟨41 63 93], which unsurprisingly is in the direction the 2-axis points. This move actually takes us off the chart, way down here.

Now let’s observe the difference in distances (see Figure 3f). Notice how the distance between the maps separated by a change in 5-term is the smallest, the maps separated by a change in 3-term have the medium-sized distance, and maps separated by a change in the 2-term have the largest distance. This tells us that steps along the 3-axis are larger than steps along the 5-axis, and steps along the 2-axis are larger still. The relationship between these sizes is that the 3-axis step has been divided by the binary logarithm of 3, written log₂3, which is approximately 1.585, while the 5-axis step has been divided by the binary logarithm of 5, written log₂5, and which is approximately 2.322. The 2-axis step can also be thought of as having been divided by the binary logarithm of its prime, but because log₂2 is exactly 1, and dividing by 1 does nothing, the scaling has no effect on the 2-axis.

The reason Paul chose this particular scaling scheme is that it causes those ETs which are closer to JI to appear closer to the center of the diagram (and this is a useful property to organize ETs by). How does this work? Well, let’s look into it.

Remember that near-just ETs have maps whose terms are in close proportion to log(2:3:5). ET maps use only integers, so they can only approximate this ideal, but a theoretical pure JI map would be ⟨log₂2 log₂3 log₂5]. If we scaled this theoretical JI map by this scaling scheme, then, we’d get 1:1:1, because we’re just dividing things by themselves: log₂2/log₂2:log₂3/log₂3:log₂5/log₂5 = 1:1:1. This tells us that we should find this theoretical JI map at the point arrived at by moving exactly the same amount along the 2-axis, 3-axis, and 5-axis. Well, if we tried that, these three movements would cancel each other out: we’d draw an equilateral triangle and end up exactly where we started, at the origin, or in other words, at pure JI. Any other ET approximating but not exactly log(2:3:5) will be scaled to proportions not exactly 1:1:1, but approximately so, like maybe 1:0.999:1.002, and so you’ll move in something close to an equilateral triangle, but not exactly, and land in some interesting spot that’s not quite in the center. In other words, we scale the axes this way so that we can compare the maps not in absolute terms, but in terms of what direction and by how much they deviate from JI (see Figure 3g).

For example, let’s scale our 12-ET example:

- 12/log₂2 = 12

- 19/log₂3 ≈ 11.988

- 28/log₂5 ≈ 12.059

Clearly, 12:11.988:12.059 is quite close to 1:1:1. This checks out with our knowledge that it is close to JI, at least in the 5-limit.

But if instead we picked some random alternate mapping of 12-ET, like ⟨12 23 25], looking at those integer terms directly, it may not be obvious how close to JI this map is. However, upon scaling them:

- 12/log₂2 = 12

- 23/log₂3 ≈ 14.511

- 25/log₂5 ≈ 10.767

It becomes clear how far this map is from JI.

So what really matters here are the little differences between these numbers. Everything else cancels out. That 12-ET’s scaled 3-term, at ≈11.988, is ever-so-slightly less than 12, indicates that prime 3 is mapped ever-so-slightly flat. And that its 5-term, at ≈12.059, is slightly more than 12, indicates that prime 5 is mapped slightly sharp in 12. This checks out with the placement of 12 on the diagram: ever-so-slightly below and to the left of the horizontal midline, due to the flatness of the 3, and slightly further still to the left, due to the sharpness of the 5.

We can imagine that if we hadn’t scaled the steps, as in our initial naive guess, we’d have ended up nowhere near the center of the diagram. How could we have, if the steps are all the same size, but we’re moving 28 of them to the left, but only 12 and 19 of them to the bottom left and top right? We’d clearly end up way, way further to the left, and also above the horizontal midline. And this is where pretty much any near-just ET would get plotted, because 3 being bigger than 2 would dominate its behavior, and 5 being larger still than 3 would dominate its behavior.

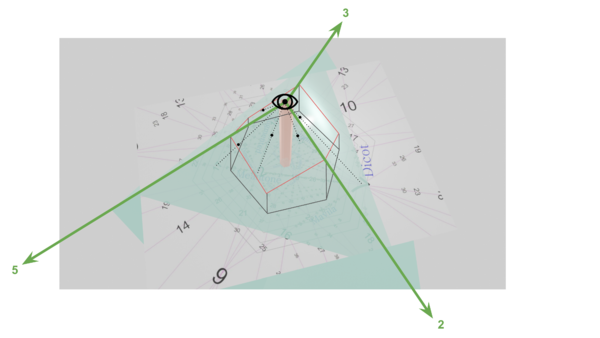

perspective

The truth about distances between related ETs on the PTS diagram is actually slightly even more complicated than that, though; as we mentioned, the scaled axes are only the first difference from our initial guess. In addition to the effect of the scaling of the axes, there is another effect, which is like a perspective effect. Basically, as ETs get more complex, you can think of them as getting farther and farther away; to suggest this, they are printed smaller and smaller on the page, and the distances between them appear smaller and smaller too.

Remember that 5-limit JI is 3D, but we’re viewing it on a 2D page. It’s not the case that its axes are flat on the page. They’re not literally occupying the same plane, 120° apart from each other. That’s just not how axes typically work, and it’s not how they work here either! The 5-axis is perpendicular to the 2-axis and 3-axis just like typical Cartesian space. Again, we’re looking only at the positive coordinates, which is to say that this is only the +++ octant of space, which comes to a point at the origin (0,0,0) like the corner of a cube. So you should think of this diagram as showing that cubic octant sticking its corner straight out of the page at us, like a triangular pyramid. So we’re like a tiny little bug, situated right at the tip of that corner, pointing straight down the octant’s interior diagonal, or in other words the line equidistant from three axes, the line which we understand represents theoretically pure JI. So we see that in the center of the page, represented as a red hexagram, and then toward the edges of the page is our peripheral vision. (See Figure 3h.)

PTS doesn’t show the entire tuning cube. You can see evidence of this in the fact that some numerals have been cut off on its edges. We’ve cropped things around the central region of information, which is where the ETs best approximating JI are found (note how close 53-ET is to the center!). Paul added some concentric hexagons to the center of his diagram, which you could think of as concentric around that interior diagonal, or in other words, are defined by gradually increasing thresholds of deviations from JI for any one prime at a time.

No maps past 99-ET are drawn on this diagram. ETs with that many steps are considered too complex (read: big numbers, impractical) to bother cluttering the diagram with. Better to leave the more useful information easier to read.

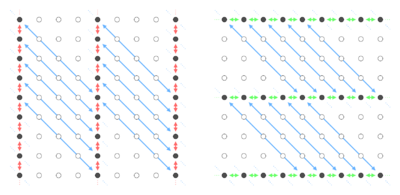

Okay, but what about the perspective effect? Right. So every step further away on any axis, then, appears a bit smaller than the previous step, because it’s just a bit further away from us. And how much smaller? Well, the perspective effect is such that, as seen on this diagram, the distances between n-ETs are twice the size of the distances between 2n-ETs.

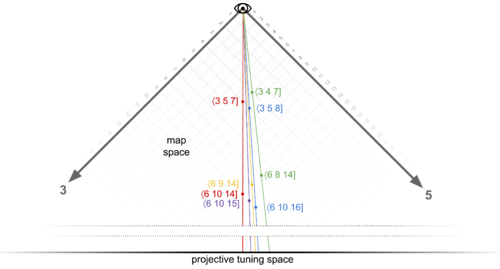

Moreover, there’s a special relationship between the positions of n-ETs and 2n-ETs, and indeed between n-ETs and 3n-ETs, 4n-ETs, etc. To understand why, it’s instructive to plot it out (see Figure 3i).

For simplicity, we’re looking at the octant cube here from the angle straight on to the 2-axis, so changes to the 2-terms don’t matter here. At the top is the origin; that’s the point at the center of PTS. Close-by, we can see the map ⟨3 5 7], and two closely related maps ⟨3 4 7] and ⟨3 5 8]. Colored lines have been drawn from the origin through these points to the black line in the top-right, which represents the page; this is portraying how if our eye is at that origin, where on the page these points would appear to be.

In between where the colored lines touch the maps themselves and the page, we see a cluster of more maps, each of which starts with 6. In other words, these maps are about twice as far away from us as the others. Let’s consider ⟨6 10 14] first. Notice that each of its terms is exactly 2x the corresponding term in ⟨3 5 7]. In effect, ⟨6 10 14] is redundant with ⟨3 5 7]. If you imagine doing a mapping calculation or two, you can easily convince yourself that you’ll get the same answer as if you’d just done it with ⟨3 5 7] instead and then simply divided by 2 one time at the end. It behaves in the exact same way as ⟨3 5 7] in terms of the relationships between the intervals it maps, the only difference being that it needlessly includes twice as many steps to do so, never using every other one. So we don’t really care about ⟨6 10 14]. Which is great, because it’s hidden exactly behind ⟨3 5 7] from where we’re looking.

The same is true of the map pair ⟨3 4 7] and ⟨6 8 14], as well as of ⟨3 5 8] and ⟨6 10 16]. Any map whose terms have a common divisor other than 1 is going to be redundant in this sense, and therefore hidden. You can imagine that even further past ⟨3 5 7] you’ll find ⟨9 15 21], ⟨12 20 28], and so on, and these are are called contorted maps[6]. More on those later. What’s important to realize here is that Paul found a way to collapse 3 dimensions worth of information down to 2 dimensions without losing anything important. Each of these lines connecting redundant ETs have been projected onto the page as a single point. That’s why the diagram is called "projective" tuning space.

Now, to find a 6-ET with anything new to bring to the table, we’ll need to find one whose terms don’t share a common factor. That’s not hard. We’ll just take one of the ones halfway between the ones we just looked at. How about ⟨6 11 14], which is halfway between ⟨6 10 14] and ⟨6 12 14]. Notice that the purple line that runs through it lands halfway between the red and blue lines on the page. Similarly, ⟨6 10 15] is halfway between ⟨6 10 14] and ⟨6 10 16], and its yellow line appears halfway between the red and green lines on the page. What this is demonstrating is that halfway between any pair of n-ETs on the diagram, whether this pair is separated along the 3-axis or 5-axis, you will find a 2n-ET. We can’t really demonstrate this with 3-ET and 6-ET on the diagram, because those ETs are too inaccurate; they’ve been cropped off. But if we return to our 40-ET example, that will work just fine.

I’ve circled every 40-ET visible in the chart (see Figure 3j). And you can see that halfway between each one, there’s an 80-ET too. Well, sometimes it’s not actually printed on the diagram[7], but it’s still there. You will also notice that if we also land right about on top of 20-ET and 10-ET. That’s no coincidence! Hiding behind that 20-ET is a redundant 40-ET whose terms are all 2x the 20-ET’s terms, and hiding behind the 10-ET is a redundant 40-ET whose terms are all 4x the 40-ET’s terms (and also a redundant 20-ET and a 30-ET, and 50-ET, 60-ET, etc. etc. etc.)

Also, check out the spot halfway between our two 17-ETs: there’s the 34-ET we briefly mused about earlier, which would solve 17’s problem of approximating prime 5 by subdividing each of its steps in half. We can confirm now that this 34-ET does a superb job at approximating prime 5, because it is almost vertically aligned with the JI red hexagram.

Just as there are 2n-ETs halfway between n-ETs, there are 3n-ETs a third of the way between n-ETs. Look at these two 29-ETs here. The 58-ET is here halfway between them, and two 87-ETs are here each a third of the way between.

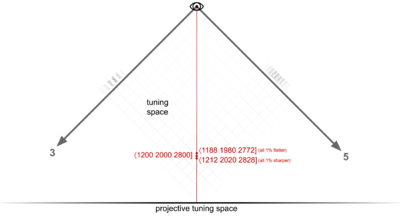

map space vs. tuning space

So far, we’ve been describing PTS as a projection of map space, which is to say that we’ve been thinking of maps as the coordinates. We should be aware that tuning space is a slightly different structure. In tuning space, coordinates are not maps, but tunings, specified in cents, octaves, or some other unit of pitch. So a coordinate might be ⟨6 10 14] in map space, but ⟨1200 2000 2800] in tuning space.

Both tuning space and map space project to the identical result as seen in Paul’s diagram, which is how we’ve been able to get away without distinguishing them thus far.

Why did I do this to you? Well, I decided map space was conceptually easier to introduce than tuning space. Paul himself prefers to think of this diagram as a projection of tuning space, however, so I don’t want to leave this material before clarifying the difference. Also, there are different helpful insights you can get from thinking of PTS as tuning space. Let’s consider those now.

The first key difference to notice is that we can normalize coordinates in tuning space, so that the first term of every coordinate is the same, namely, one octave, or 1200 cents. For example, note that while in map space, ⟨3 5 7] is located physically in front of ⟨6 10 14], in tuning space, these two points collapse to literally the same point, ⟨1200 2000 2800]. This can be helpful in a similar way to how the scaled axes of PTS help us visually compare maps’ proximity to the central JI spoke: they are now expressed closer to in terms of their deviation from JI, so we can more immediately compare maps to each other, as well as individually directly to the pure JI primes, as long as we memorize the cents values of those (they’re 1200, 1901.955, and 2786.314). For example, in map space, it may not be immediately obvious that ⟨6 9 14] is halfway between ⟨3 5 7] and ⟨3 4 7], but in tuning space it is immediately obvious that ⟨1200 1800 2800] is halfway between ⟨1200 2000 2800] and ⟨1200 1600 2800].

So if we take a look at a cross-section of projection again, but in terms of tuning space now (see Figure 3k), we can see how every point is about the same distance from us.

The other major difference is that tuning space is continuous, where map space is discrete. In other words, to find a map between ⟨6 10 14] and ⟨6 9 14], you’re subdividing it by 2 or 3 and picking a point in between, that sort of thing. But between ⟨1200 2000 2800] and ⟨1200 1800 2800] you’ve got an infinitude of choices smoothly transitioning between each other; you’ve basically got knobs you can turn on the proportions of the tuning of 2, 3, and 5. Everything from from ⟨1200 1999.999 2800] to ⟨1200 1901.955 2800] to ⟨1200 1817.643 2800] is along the way.

But perhaps even more interesting than this continuous tuning space that appears in PTS between points is the continuous tuning space that does not appear in PTS because it exists within each point, that is, exactly out from and deeper into the page at each point. In tuning space, as we’ve just established, there are no maps in front of or behind each other that get collapsed to a single point. But there are still many things that get collapsed to a single point like this, but in tuning space they are different tunings (see Figure 3l). For example, ⟨1200 1900 2800] is the way we’d write 12-ET in tuning space. But there are other tunings represented by this same point in PTS, such as ⟨1200.12 1900.19 2800.28] (note that in order to remain at the same point, we’ve maintained the exact proportions of all the prime tunings). That tuning might not be of particular interest. I just used it as a simple example to illustrate the point. A more useful example would be ⟨1198.440 1897.531 2796.361], which by some algorithm is the optimal tuning for 12-ET (minimizes error across primes or intervals); it may not be as obvious from looking at that one, but if you check the proportions of those terms with each other, you will find they are still exactly 12:19:28.

The key point here is that, as we mentioned before, the problems of tuning and tempering are largely separate. PTS projects all tunings of the same temperament to the same point. This way, issues of tuning are completely hidden and ignored on PTS, so we can focus instead on tempering.

regions

We’ve shown that ETs with the same number that are horizontally aligned differ in their mapping of 5, and ETs with the same number that are aligned on the 3-axis running bottom left to top right differ in their mapping of 3. These basic relationships can be extrapolated to be understood in a general sense. ETs found in the center-left map 5 relatively big and 2 and 3 relatively small. ETs found in the top-right map 3 relatively big and 2 and 5 relatively small. ETs found in the bottom-right map 2 relatively big and 3 and 5 relatively small. And for each of these three statements, the region on the opposite side maps things in the opposite way.

So: we now know which point is ⟨12 19 28], and we know a couple of 17’s, 40’s and a 41. But can we answer in the general case? Given an arbitrary map, like ⟨7 11 16], can we find it on the diagram? Well, you may look to the first term, 7, which tells you it’s 7-ET. There’s only one big 7 on this diagram, so it’s probably that. (You’re right). But that one’s easy. The 7 is huge.

What if I gave you ⟨43 68 100]. Where’s 43-ET? I’ll bet you’re still complaining: the map expresses the tempering of 2, 3, and 5 in terms of their shared generator, but doesn’t tell us directly which primes are sharp, and which primes are flat, so how could we know in which region to look for this ET?

The answer to that is, unfortunately: that’s just how it is. It can be a bit of a hunt sometimes. But the chances are, in the real world, if you’re looking for a map or thinking about it, then you probably already have at least some other information about it to help you find it, whether it’s memorized in your head, or you’re reading it off the results page for an automatic temperament search tool.

Probably you have the information about the primes’ tempering; maybe you get lucky and a 43 jumps out at you but it’s not the one you’re looking for, but you can use what you know about the perspectival scaling and axis directions and log-of-prime scaling to find other 43’s relative to it.

Or maybe you know which commas ⟨43 68 100] tempers out, so you can find it along the line for that comma’s temperament.

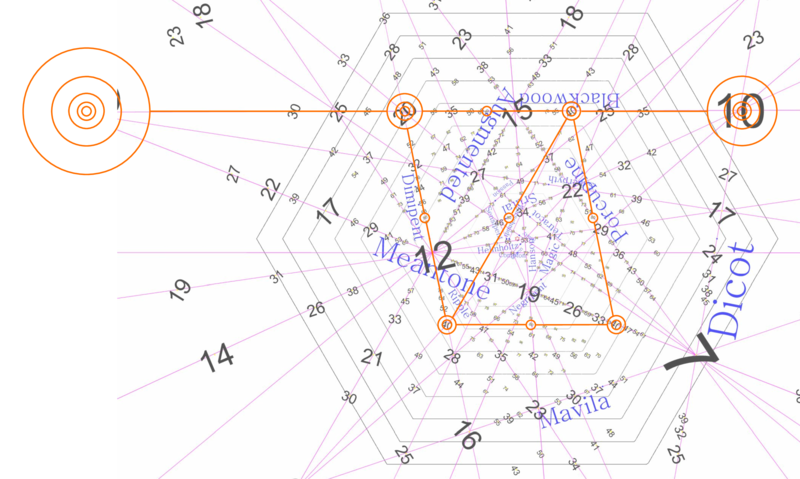

linear temperaments

We're about to take our first look at temperaments beyond mere equal temperaments. By the end of this section, you'll be able to explain the musical meaning of the patterns in the numerals along lines in PTS, the labels of these lines, as well as what's happening at their intersections and what their slopes mean. In other words, pretty much all of the major remaining visual elements on PTS should make sense to you.

temperament lines

So we understand the shape of projective tuning space. And we understand what points are in this space. But what about the magenta lines, now?

So far, we’ve only mentioned one of these lines: the one labelled “meantone”, noting that the fact that 12-ET and 17-ET appear on it means that either of them tempers out the meantone comma. In other words, this line represents the meantone temperament.

For another example, the line on the right side of the diagram running almost vertically which has the other 17-ET we looked at, as well as 10-ET and 7-ET, is labeled “dicot”, and so this line represents the dicot temperament, and unsurprisingly all of these ET’s temper out the dicot comma.

Simply put, lines on PTS are temperaments. Specifically, they are abstract regular temperaments. If you are a student of historical temperaments, you may be familiar with e.g. quarter-comma meantone; to an RTT practitioner, this is actually a specific tuning of the meantone temperament. Meantone is an abstract temperament, which encompasses a range of other possible temperaments and tunings.

If you’re new to RTT, all of the other temperaments besides meantone, like “dicot”, “porcupine”, and “mavila”, are probably unfamiliar and their names may seem sort of random or bizarre looking. Well, you’re not wrong about the names being random and bizarre. But mathematically and musically, these temperaments are every bit as much real and of interest as meantone. One day you too may compose a piece or write an academic paper about porcupine temperament.

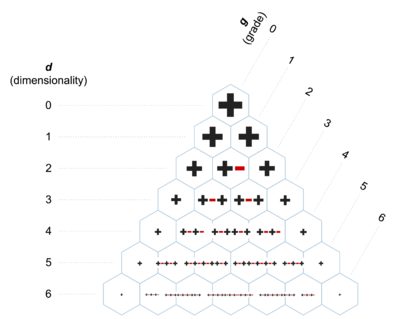

But hold up now: points are ETs, which are temperaments, too, right? Well, yes, that’s still true. But while points are equal, or rank-1 temperaments, the lines represent what we call rank-2 temperaments. It may be helpful to differentiate the names in your mind in terms of their geometric dimensionality. Recall that projective tuning space has compressed all our information by one dimension; every point on our diagram is actually a line radiating out from our eye. So a rank-1 temperament is really a line, which is one-dimensional; rank-1, 1D. And the rank-2 temperaments, which are seen as lines in our diagram, are truly planes coming up out of the page, and planes are of course two-dimensional; rank-2, 2D. If you wanted to, you could even say 5-limit JI was a rank-3 temperament, because that’s this entire space, which is 3-dimensional; rank-3, 3D.

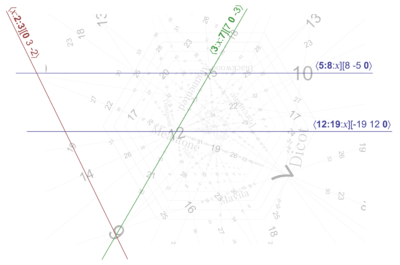

“Rank” has a slightly different meaning than dimension, but that’s not important yet. We’ll define rank, and discuss what exactly a rank-2 or -3 temperament means later. For now, it’s enough to know that each temperament line on this 5-limit PTS diagram is defined by tempering out a comma which has the same name. For now, we’re still focusing on visually how to navigate PTS. So the natural thing to wonder next, then, is what’s up with the slopes of all these temperament lines?

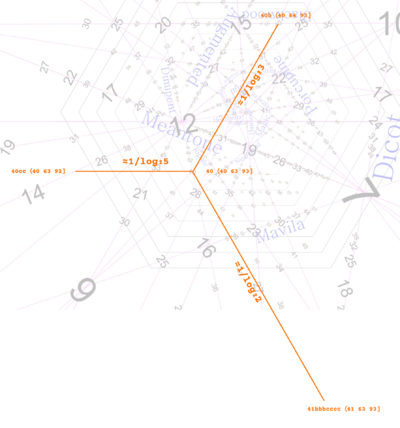

Let’s begin with a simple example: the perfectly horizontal line that runs through just about the middle of the page, through the numeral 12, labelled “compton”. What’s happening along this line? Well, as we know, moving to the left means tuning 5 sharper, and moving to the right means tuning 5 flatter. But what about 2 and 3? Well, they are changing as well: 2 is sharp in the bottom right, and 3 is sharp in the top right, so when we move exactly rightward, 2 and 3 are both getting sharper (though not as directly as 5 is getting flatter). But the critical thing to observe here is that 2 and 3 are sharpening at the exact same rate. Therefore the approximations of primes 2 and 3 are in a constant ratio with each other along horizontal lines like this. Said another way, if you look at the 2 and 3 terms for any ET’s map on this line, the ratio between its term for 2 and 3 will be identical.

Let’s grab some samples to confirm. We already know that 12-ET here looks like ⟨12 19] (I’m dropping the 5 term for now). The 24-ET here looks like ⟨24 38], which is simply 2×⟨12 19]. The 36-ET here looks like ⟨36 57] = 3×⟨12 19]. And so on. So that’s why we only see multiples of 12 along this line: because 12 and 19 are co-prime, so the only other maps which could have them in the same ratio would be multiples of them.

Let’s look at the other perfectly horizontal line on this diagram. It’s found about a quarter of the way down the diagram, and runs through the 10-ET and 20-ET we looked at earlier. This one’s called “blackwood”. Here, we can see that all of its ETs are all multiples of 5. In fact, 5-ET itself is on this line, though we can only see a sliver of its giant numeral off the left edge of the diagram. Again, all of its maps have locked ratios between their mappings of prime 2 and prime 3: ⟨5 8], ⟨10 16], ⟨15 24], ⟨20 32], ⟨40 64], ⟨80 128], etc. You get the idea.

So what do these two temperaments have in common such that their lines are parallel? Well, they’re defined by commas, so why don’t we compare their commas. The compton comma is [-19 12 0⟩, and the blackwood comma is [8 -5 0⟩[8]. What sticks out about these two commas is that they both have a 5-term of 0. This means that when we ask the question “how many steps does this comma map to in a given ET”, the ET’s mapping of 5 is irrelevant. Whether we check it in ⟨40 63 93] or ⟨40 63 94], the result is going to be the same. So if ⟨40 63 93] tempers out the blackwood comma, then ⟨40 63 94] also tempers out the blackwood comma. And if ⟨24 38 56] tempers out compton, then ⟨24 38 55] tempers out compton. And so on.

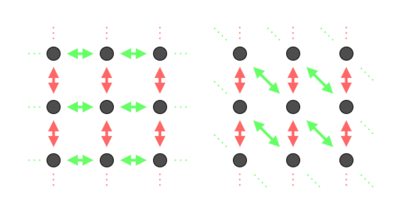

Similar temperaments can be found which include only 2 of the 3 primes at once. Take “augmented”, for instance, running from bottom-left to top-right. This temperament is aligned with the 3-axis. This tells us several equivalent things: that relative changes to the mapping of 3 are irrelevant for augmented temperament, that the augmented comma has no 3’s in its prime factorization, and the ratios of the mappings of 2 and 5 are the same for any ET along this line. Indeed we find that the augmented comma is [7 0 -3⟩, or 128/125, which has no 3’s. And if we sample a few maps along this line, we find ⟨12 19 28], ⟨9 14 21], ⟨15 24 35], ⟨21 33 48], ⟨27 43 63], etc., for which there is no pattern to the 3-term, but the 2- and 5-terms for each are in a 3:7 ratio.

There are even temperaments whose comma includes only 3’s and 5’s, such as “bug” temperament, which tempers out 27/25, or [0 3 -2⟩. If you look on this PTS diagram, however, you won’t find bug. Paul chose not to draw it. There are infinite temperaments possible here, so he had to set a threshold somewhere on which temperaments to show, and bug just didn’t make the cut in terms of how much it distorts harmony from JI. If he had drawn it, it would have been way out on the left edge of the diagram, completely outside the concentric hexagons. It would run parallel to the 2-axis, or from top-left to bottom-right, and it would connect the 5-ET (the huge numeral which is cut off the left edge of the diagram so that we can only see a sliver of it) to the 9-ET in the bottom left, running through the 19-ET and 14-ET in-between. Indeed, these ET maps — ⟨9 14 21], ⟨5 8 12], ⟨19 30 45], and ⟨14 22 33] — lock the ratio between their 3-terms and 5-terms, in this case to 2:3.

Those are the three simplest slopes to consider, i.e. the ones which are exactly parallel to the axes (see Figure 4a). But all the other temperament lines follow a similar principle. Their slopes are a manifestation of the prime factors in their defining comma. If having zero 5’s means you are perfectly horizontal, then having only one 5 means your slope will be close to horizontal, such as meantone [-4 4 -1⟩ or helmholtz [-15 8 1⟩. Similarly, magic [-10 -1 5⟩ and würschmidt [17 1 -8⟩, having only one 3 apiece, are close to parallel with the 3-axis, while porcupine [1 -5 3⟩ and ripple [-1 8 -5⟩, having only one 2 apiece, are close to parallel with the 2-axis.

Think of it like this: for meantone, a change to the mapping of 5 doesn’t make near as much of a difference to the outcome as does a change to the mapping of 2 or 3, therefore, changes along the 5-axis don’t have near as much of an effect on that line, so it ends up roughly parallel to it.

scale trees

Patterns, patterns, everywhere. PTS is chock full of them. One pattern we haven’t discussed yet is the pattern made by the ETs that fall along each temperament line.

Let’s consider meantone as our first example. Notice that between 12 and 7, the next-biggest numeral we find is 19, and 12+7=19. Notice in turn that between 12 and 19 the next-biggest numeral is 31, and 12+19=31, and also that between 19 and 7 the next-biggest numeral is 26, and 19+7=26. You can continue finding deeper ETs indefinitely following this pattern: 43 between 12 and 31, 50 between 31 and 19, 45 between 19 and 26, 33 between 26 and 7. In fact, if we step back a bit, remembering that the huge numeral just off the left edge is a 5, we can see that 12 is there in the first place because 5+7=12.

This effect is happening on every other temperament line. Look at dicot. 10+7=17. 10+17=27. 17+7=24. Etc.[9]

To fully understand why this is happening, we need a crash course in mediants, and the The Stern-Brocot tree.

The mediant of two fractions [math]\displaystyle{ \frac ab }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac cd }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{a+c}{b+d} }[/math]. It’s sometimes called the freshman’s sum because it’s an easy mistake to make when first learning how to add fractions. And while this operation is certainly not equivalent to adding two fractions, it does turn out to have other important mathematical properties. The one we’re leveraging here is that the mediant of two numbers is always greater than one and less than the other. For example, the mediant of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 35 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 23 }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 58 }[/math], and it’s easy to see in decimal form that 0.625 is between 0.6 and 0.666.

The Stern-Brocot tree is a helpful visualization of all these mediant relations. Flanking the part of the tree we care about — which comes up in the closely-related theory of MOS scales, where it is often referred to as the “scale tree” — are the extreme fractions [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 01 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 11 }[/math]. Taking the mediant of these two gives our first node: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 12 }[/math]. Each new node on the tree drops an infinitely descending line of copies of itself on each new tier. Then, each node branches to either side, connecting itself to a new node which is the mediant of its two adjacent values. So [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 01 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 12 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 13 }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 12 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 11 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 23 }[/math]. In the next tier, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 01 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 13 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 14 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 13 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 12 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 12 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 23 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 35 }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 23 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 11 }[/math] become [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 34 }[/math].[10] The tree continues forever.

So what does this have to do with the patterns along the temperament lines in PTS? Well, each temperament line is kind of like its own section of the scale tree. The key insight here is that in terms of meantone temperament, there’s more to 7-ET than simply the number 7. The 7 is just a fraction’s denominator. The numerator in this case is 3. So imagine a [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math] floating on top of the 7-ET there. And there’s more to 5-ET than simply the number 5, in that case, the fraction is the [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math]. So the mediant of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{12} }[/math]. And if you compare the decimal values of these numbers, we have 0.4, 0.429, and 0.417. Success: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{12} }[/math] is between [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math] on the meantone line. You may verify yourself that the mediant of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{12} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{8}{19} }[/math], is between them in size, as well as [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{7}{17} }[/math] being between [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{12} }[/math] in size.

In fact, if you followed this value along the meantone line all the way from [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math], it would vary continuously from 0.4 to 0.429; the ET points are the spots where the value happens to be rational.

Okay, so it’s easy to see how all this follows from here. But where the heck did I get [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math] in the first place? I seemed to pull them out of thin air. And what the heck is this value?

generators

The answer to both of those questions is: it’s the generator (in this case, the meantone generator).

A generator is an interval which generates a temperament. Again, if you’re already familiar with MOS scales, this is the same concept. If not, all this means is that if you repeatedly move by this interval, you will visit the pitches you can include in your tuning.

We briefly looked at generators earlier. We saw how the generator for 12-ET was about 1.059, because repeated movement is like repeated multiplication (1.059 × 1.059 × 1.059 ...) and 1.059¹² ≈ 2, 1.059¹⁹ ≈ 3, and 1.059²⁸ ≈ 5. This meantone generator is the same basic idea, but there’s a couple of important differences we need to cover.

First of all, and this difference is superficial, it’s in a different format. We were expressing 12-ET’s generator 1.059 as a frequency multiplier; it’s like 2, 3, or 5, and this could be measured in Hz, say, by multiplying by 440 if A4 was our 1/1 (1.059 away from A is 466Hz, which is #A). But the meantone generators we’re looking at now in forms like [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 25 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 37 }[/math], or [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{12} }[/math], are expressed as fractional octaves, i.e. they’re in terms of pitch, something that could be measured in cents if we multiplied by 1200 (2/5 × 1200¢ = 480¢). We have a special way of writing fractional octaves, and that’s with a backslash instead of a slash, like this: 2\5, 3\7, 5\12.

Cents and Hertz values can readily be converted between one form and the other, so it’s the second difference which is more important. It’s their size. If we do convert 12-ET’s generator to cents so we can compare it with meantone’s generator at 12-ET, we can see that 12-ET’s generator is 100¢ (log₂1.059 × 1200¢ = 100¢) while meantone’s generator at 12-ET is 500¢ (5/12 × 1200¢ = 500¢). What is the explanation for this difference?

Well, notice that meantone is not the only temperament which passes through 12-ET. Consider augmented temperament. Its generator at 12-ET is 400¢[11]. What's key here is that all three of these generators — 100¢, 500¢, and 400¢ — are multiples of 100¢.

Let’s put it this way. When we look at 12-ET in terms of itself, rather than in terms of any particular rank-2 temperament, its generator is 1\12. That’s the simplest, smallest generator which if we iterate it 12 times will touch every pitch in 12-ET. But when we look at 12-ET not as the end goal, but rather as a foundation upon which we could work with a given temperament, things change. We don’t necessarily need to include every pitch in 12-ET to realize a temperament it supports.

For example, for meantone, even if I iterated the generator only four times, starting at step 0, touching steps 5, 10, 3 (it would be 15, but we octave-reduce here, subtracting 12 to stay within 12, landing back at 15 - 12 = 3), and 8, we’d realize meantone. That’s because fourths and fifths are octave-complements, and so in a sense they are equivalent. So, moving four fourths up like this is the same thing as moving four fifths down, and we can see that gets me to the same place as if I moved one major third down, which — being 4 steps — would also take me to step 8. That's the central idea of meantone temperament, and so this is what I mean by we've "realized" it.

If we continued to iterate this 12-ET meantone generator, we would happen to eventually touch every pitch in 12-ET, because 5 and 12 are coprime; we’d continue onward from 8 to 1 (13 - 12 = 1), then 6, 11, 4, 9, 2, 7, and circle back to 0. On the other hand, augmented temperament in 12-ET could never reach most of the pitches, because 4 is not coprime with 12; the 4\12 generator is essentially 1\3, and can only reach 0, 4, and 8. From augmented temperament’s perspective, that’s acceptable, though: this set of pitches still realizes the fact that three major thirds get you back where you started, which is its whole point.

The fact that both the augmented and meantone temperament lines pass through 12-ET doesn’t mean that you need the entirety of 12-ET to play either one; it means something more like this: if you had an instrument locked into 12-ET, you could use it to play some kind of meantone and some kind of augmented. 12-ET is not necessarily the most interesting manifestation of either meantone or augmented; it’s merely the case that it technically supports either one. The most interesting manifestations of meantone or augmented may lay between ETs, and/or boast far more than 12 notes.

We mentioned that the generator value changes continuously as we move along a temperament line. So just to either side of 12-ET along the meantone line, the tuning of 2, 3, and 5 supports a generator size which in turn supports meantone, but it wouldn’t support augmented. And just to either side of 12-ET along the augmented line, the tuning of 2, 3, and 5 supports a generator which still supports augmented, but not meantone. 12-ET, we could say, is a convergence point between the meantone generator and the augmented generator. But it is not a convergence point because the two generators become identical in 12-ET, but rather because they can both be achieved in terms of 12-ET’s generator. In other words, 5\12 ≠ 4\12, but they are both multiples of 1\12.

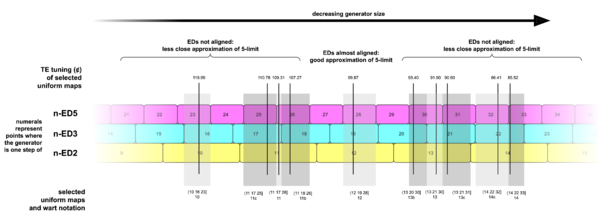

Here’s a diagram that shows how the generator size changes gradually across each line in PTS. It may seem weird how the same generator size appears in multiple different places across the space. But keep in mind that pretty much any generator is possible pretty much anywhere here. This is simply the generator size pattern you get when you lock the period to exactly 1200 cents, to establish a common basis for comparison. These are called linear temperaments. This is what enables us to produce maps of temperaments such as the one found at this Xen wiki page, or this chart here (see Figure 4b).

periods and generators

Earlier we mentioned the term “rank”. I warned you then that it wasn’t actually the same thing as dimensionality, even though we could use dimensionality in the PTS to help differentiate rank-2 from rank-1 temperaments. Now it’s time to learn the true meaning of rank: it’s how many generators a temperament has. So, it is the dimensionality of the tempered lattice; but it's still important to stay clear about the fact that it's different from the dimensionality of the original system from which you are tempering.

When we spoke of the generator for a rank-2 temperament such as meantone, we were taking advantage of the fact that the other generator is generally assumed to be the octave, and it gets its own special name: the period. It’s technically a generator too, but when we say “the” generator of a rank-2 temperament, we mean the one that’s not the period.

In rank-2 temperaments, the period usually serves as the interval of repetition. Rank-1 temperaments have only one generator, but by definition it’s some integer fraction of the interval of repetition. So, in an ET, the period is not literally a separate generator, but it may still make sense in context to refer to its interval of repetition — octave or otherwise — as the period, especially when comparing the ET with a related rank-2 temperament.

As we’ll soon see, there’s more than one way to generate a given rank-2 temperament. For example, meantone can be generated by an octave and a fourth. But it could equivalently be generated by an octave and a fifth. Or an octave and an augmented unison. It could even be generated by cycling a fourth against a fifth. And so on.

And so it’s good to have a standard form for the generators of a rank-2 temperament. One excellent standard is to set the period to an octave and the generator set to anything less than half the size of the period, as we did earlier, and again, when in this form, we call the temperament a linear temperament (not all rank-2 temperaments can be linear, e.g. if they repeat multiple times per octave, such as blackwood 5x or augmented 3x).

Let’s bring up MOS theory again. We mentioned earlier that you might have been familiar with the scale tree if you’d worked with MOS scales before, and if so, the connection was scale cardinalities, or in other words, how many notes are in the resultant scales when you continuously iterate the generator until you reach points where there are only two scale step sizes. At these points scales tend to sound relatively good, and this is in fact the definition of a MOS scale. There’s a mathematical explanation for how to know, given a ratio between the size of your generator and period, the cardinalities of scales possible; we won’t re-explain it here. The point is that the scale tree can show you that pattern visually. And so if each temperament line in PTS is its own segment of the scale tree, then we can use it in a similar way.

For example, if we pick a point along the meantone line between 46 and 29, the cardinalities will be 5, 12, 17, 29, 46, etc. If we chose exactly the point at 29, then the cardinality pattern would terminate there, or in other words, eventually we’ll hit a scale with 29 notes and instead of two different step sizes there would only be one, and there’s no place else to go from there. The system has circled back around to its starting point, so it’s a closed system. Further generator iterations will only retread notes you’ve already touched. The same would be true if you chose exactly the point at 46, except that’s where you’d hit an ET instead.

Between ETs, in the stretches of rank-2 temperament lines where the generator is not a rational fraction of the octave, theoretically those temperaments could have infinite pitches; you could continuously iterate the generator and you’d never exactly circle back to the point where you started. If bigger numbers were shown on PTS, you could continue to use those numbers to guide your cardinalities forever.

The structure when you stop iterating the meantone generator with five notes is called meantone[5]. If you were to use the entirety of 12-ET as meantone then that’d be meantone[12]. But you can also realize meantone[12] in 19-ET; in the former you have only one step size, but in the latter you have two. You can’t realize meantone[19] in 12-ET, but you could also realize it in 31-ET.

meet and join

We’ve seen how 12-ET is found at the convergence of meantone and augmented temperaments, and therefore supports both at the same time. In fact, no other ET can boast this feat. Therefore, we can even go so far as to describe 12-ET as the meeting of the meantone line and the augmented line. Using the pipe operator “|” to mean “meet”, then, we could call 12-ET “meantone|augmented”, read "meantone meet augmented". In other words, we express a rank-1 temperament in terms of two rank-2 temperaments.

For another rank-1 example, we could call 7-ET “meantone|dicot”, because it is the meeting of meantone and dicot temperaments.

We can conclude that there’s no “blackwood|compton” temperament, because those two lines are parallel. In other words, it’s impossible to temper out the blackwood comma and compton comma simultaneously. How could it ever be the case that 12 fifths take you back where you started yet also 5 fifths take you back where you started?[12]

Similarly, we can express rank-2 temperaments in terms of rank-1 temperaments. Have you ever heard the expression “two points make a line”? Well, if we choose two ETs from PTS, then there is one and only one line that runs through both of them. So, by choosing those ETs, we can be understood to be describing the rank-2 temperament along that line, or in other words, the one and only temperament whose comma both of those ETs temper out.

For example, we could choose 7-ET and 12-ET. Looking at either 12-ET or 7-ET, we can see that many, many temperament lines pass through them individually. Even more pass through them which Paul chose (via a complexity threshold) not to show. But there’s only one line which runs through both 7-ET and 12-ET, and that’s the meantone line. So of all the commas that 7-ET tempers out, and all the commas that 12-ET tempers out, there’s only a single one which they have in common, and that’s the meantone comma. Therefore we could give meantone temperament another name, and that’s “7&12”; in this case we use the ampersand operator, not the pipe. This operator is called "join", so we can read that "7 join 12".[13]

When specifying a rank-1 temperament in terms of two rank-2 temperaments, an obvious constraint is that the two rank-2 temperaments cannot be parallel. When specifying a rank-2 temperament in terms of two rank-1 temperaments, it seems like things should be more open-ended. Indeed, however, there is a special additional constraint on either method, and they’re related to each other. Let’s look at rank-2 as the join of rank-1 first.

7&12 is valid for meantone. So is 5&7, and 7&12. 12&19 and 19&7 are both fine too, and so are 5&17 and 17&12. Yes, these are all literally the same thing (though you may connote a meantone generator size on the meantone line somewhere between these two ETs). So how could we mess this one up, then? Well, here’s our first counterexamples: 5&19, 7&17, and 17&19. And what problem do all these share in common? The problem is that between 5 and 19 on the meantone line we find 12, and 12 is a smaller number than 19 (or, if you prefer, on PTS, it is printed as a larger numeral). It’s the same problem with 17&19, and with 7&17 the problem is that 12 is smaller than 17. It’s tricky, but you have to make sure that between the two ETs you join there’s not a smaller ET (which you should be joining instead). The reason why is out of scope to explain here, but we’ll get to it eventually.

I encourage you to spend some time playing around with Graham Breed's online RTT tool. For example, at http://x31eq.com/temper/net.html you can enter 12&19 in the "list of steps to the octave" field and 5 in the "limit" field and Submit, and you'll be taken to a results page for meantone.

And the related constraint for rank-1 from two rank-2 is that you can’t choose two temperaments whose names are printed smaller on the page than another temperament between them. More on that later.

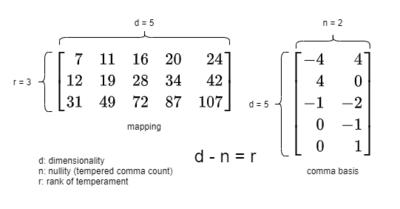

matrices

From the PTS diagram, we can visually pick out rank-1 temperaments at the meetings of rank-2 temperaments as well as rank-2 temperaments as the joinings of rank-1 temperaments. But we can also understand these results through covectors and vectors. And we're going to need to learn how, because PTS can only take us so far. 5-limit PTS is good for humans because we live in a physically 3-dimensional world (and spend a lot of time sitting in front of 2D pages on paper and on computer screens), but as soon as you want to start working in 7-limit harmony, which is 4D, visual analogies will begin to fail us, and if we’re not equipped with the necessary mathematical abstractions, we’ll no longer be able to effectively navigate.

Don’t worry: we’re not going 4D just yet. We’ve still got plenty we can cover using only the 5-limit. But we may put away PTS for a couple sections. It’s matrix time. By the end of this section, you'll understand how to represent a temperament in matrix form, how to interpret them, notate them, and use them, as well as how to apply important transformations between different kinds of these matrices.

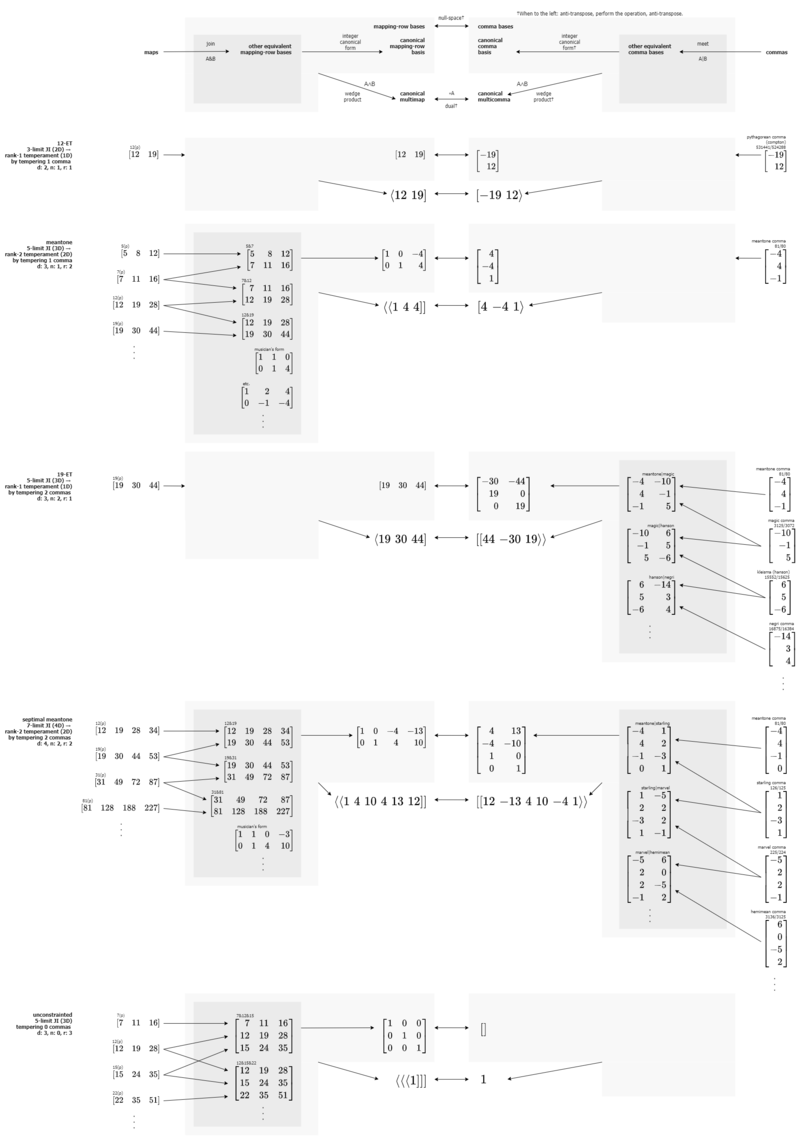

mapping-row bases and comma bases

19-ET. Its map is ⟨19 30 44]. We also now know that we could call it “meantone|magic”, because we find it at the meeting of the meantone and magic temperament lines. But how would we mathematically, non-visually make this connection?

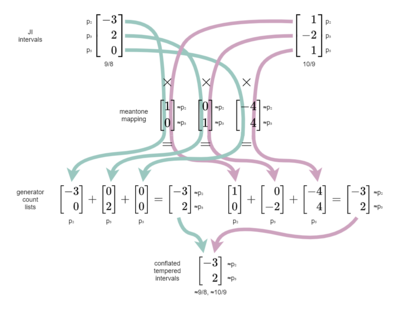

The first critical step is to recall that temperaments are defined by commas, which can be expressed as vectors. So, we can represent meantone using the meantone comma, [-4 4 -1⟩, and magic using the magic comma [-10 -1 5⟩.

The meet of two vectors can be represented as a matrix. If a vector is like a list of numbers, a matrix is a table of them. Technically, vectors are vertical lists of numbers, or columns, so when we put meantone and magic together, we get a matrix that looks like this:

[math]\displaystyle{ \left[ \begin{array} {rrr} -4 & -10 \\ 4 & -1 \\ -1 & 5 \end{array} \right] }[/math]

We call such a matrix a comma basis. The plural of “basis” is “bases”, but pronounced like BAY-sees (/ˈbeɪ siz/).

Now how in the world could that matrix represent the same temperament as ⟨19 30 44]? Well, they’re two different ways of describing it. ⟨19 30 44], as we know, tells us how many generator steps it takes to reach each prime approximation. This matrix, it turns out, is an equivalent way of stating the same information. This matrix is a minimal representation of the null-space of that mapping, or in other words, of all the commas it tempers out. (Don't worry about the word "mapping" just yet; for now, just imagine I'm writing "map". We'll explain the difference very soon.).

This was a bit tricky for me to get my head around, so let me hammer this point home: when you say "the null-space", you're referring to the entire infinite set of all commas that a mapping tempers out, not only the two commas you see in any given basis for it. Think of the comma basis as one of many valid sets of instructions to find every possible comma, by adding or subtracting these two commas from each other[14]. The math term for adding and subtracting vectors like this, which you will certainly see plenty of as you explore RTT, is "linear combination". It should be visually clear from the PTS diagram that this 19-ET comma basis couldn't be listing every single comma 19-ET tempers out, because we can see there are at least four temperament lines that pass through it (there are actually infinity of them!). But so it turns out that picking two commas is perfectly enough; every other comma that 19-ET tempers out could be expressed in terms of these two!

Try one. How about the hanson comma, [6 5 -6⟩. Well that one’s too easy! Clearly if you go down by one magic comma to [10 1 -5⟩ and then up by one meantone comma you get one hanson comma. What you’re doing when you’re adding and subtracting multiples of commas from each other like this is technically called “Gauss-Jordan elimination”. Feel free to work through any other examples yourself.

A good way to explain why we don’t need three of these commas is that if you had three of them, you could use any two of them to create the third, and then subtract the result from the third, turning that comma into a zero vector, or a vector with only zeroes, which is pretty useless, so we could just discard it.

And a potentially helpful way to think about why any other interval arrived at through linear combinations of the commas in a basis would also be a valid column in the basis is this: any of these interval vectors, by definition, is mapped to zero steps by the mapping. So any combination of them will also map to zero steps, and thus be a comma that is tempered out by the temperament.

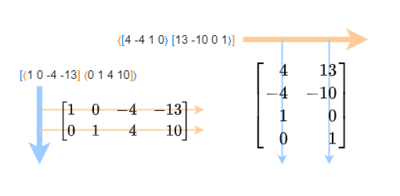

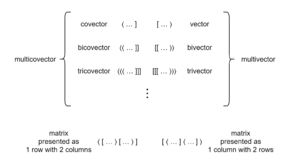

When written with the ⟨] notation, we’re expressing maps in “covector” form, or in other words, as the opposite of vectors. But we can also think of maps in terms of matrices. If vectors are like matrix columns, maps are like matrix rows. So while we have to write [-4 4 -1⟩ vertically when in matrix form, ⟨19 30 44] stays horizontal.