Equal-step tuning

An equal-step tuning, equal tuning, or equal division (ED) is a periodic tuning system where the distance between adjacent steps is of constant size. The size of this single step is given explicitly (e.g. 88-cent equal tuning) or as a fraction of a larger interval (e.g. 13 equal divisions of the octave). Any interval, rational/just, or irrational, may be used as the basis for an equal tuning, although divisions of the octave are most common, leading to edo systems. When a just interval is equally divided, it is assumed none of the resulting intervals are just, because if the interval has a rational root it is seen as a division of that root.

When a tuning is called n-tone equal temperament (abbreviated n-tet or n-et), this usually means "n divisions of 2/1, the octave, or some approximation thereof", but it also implies a mindset of temperament – that is, of a JI-approximation-based understanding of the scale. If you are wondering how equal divisions of the octave can become associated with temperaments, the page EDOs to ETs may help clarify.

There are many reasons why one might choose to not consider JI approximations when dealing with equal tunings, and thus not treat equal tunings as temperaments. In such case, the less theory-laden term edo (occasionally written ed2), meaning equal divisions of the octave (or equal divisions of 2/1), leaves comparison to JI out of the picture, aside from the octave itself (which is assumed to be just). There are other less standard terms, many in the Tonalsoft Encyclopedia. More generally, the term ed-p can be used, where p is any frequency ratio. For example, the equal-tempering of the Bohlen–Pierce scale may be referred to as 13ed3, for 13 equal divisions of 3/1 (the 3rd harmonic).

As the steps are tuned to be equal, equal scales may be taken to close anywhere composers wish them to. Barring the convention of closing equal divisions of particular just intervals at those stated just intervals, there are infinite synonymous names for each equal scale.

As there are infinitely many intervals, there are infinitely many equal scales. Barring technicalities, there are large quantities of perceivably different equal scales. Seeing such a diverse menagerie at their disposal, some composers choose to combine multiple equal tunings sequentially or simultaneously.

An equal-step tuning is an arithmetic and harmonotonic tuning. In terms of what musical resource is divided, it divides pitch, so another term for equal-step tuning is equal pitch division (EPD). Since pitch is the most commonly divided resource, this can be shortened to just equal division (ED).

Formula

To find the step size of n-ed-p in terms of cents, divide the cents of p by n. The size s of k steps of n-ed-p (k\n <p>) is

[math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle s = 1200 \log_2 (p) \cdot k/n }[/math]

To find the step size of n-edo in terms of frequency ratio, take the n-th root of p. For example, the step of 12edo is 21/12 (≈ 1.059). So the ratio c of k steps of n-ed-p is

[math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle c = p^{k/n} }[/math]

In particular, when k is 0, c is simply 1, because any number to the 0th power is 1. And when k = n, c is simply p, because any number to the 1st power is itself.

Lookalike equal divisions

What do 12ed2, 19ed3, and 28ed5 all have in common? They are all approximately the same scale. This happens because 12ed2 is an accurate temperament (for its size) that contains relatively close approximations of 3/1 and 5/1. In contrast, 11ed2 does not correspond closely to any equal division of 3/1 or 5/1.

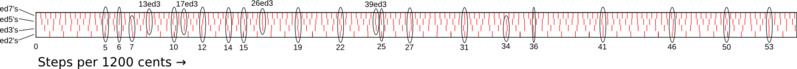

The following plot shows equal divisions of 2/1, 3/1, 5/1, and 7/1, and points out some instances when three or more of them happen to be close together. Note that any equal division of 2/1 is automatically an equal division of 4/1; and if something is simultaneously a good equal division of both 2/1 and 3/1, then it is a good equal division of 6/1 as well.

(Unlimited resolution version: equal.svg)

For the mathematically inclined, this kind of diagram is closely related to the Riemann zeta function.

Catalog of equal-step tunings

Equal divisions

- Includes Edp for p with a Wilson height ≤ 10 and integer limit ≤ 8 (plus some extras due to strong consensus for their inclusion).

- Ed9/8 (… of the major whole tone)

- Ed6/5 (… of the classic minor third)

- Ed5/4 (… of the classic major third)

- Ed4/3 (… of the perfect fourth)

- EDF (… of the perfect fifth, 3/2)

- most famously approximates Carlos Alpha, Beta and Gamma, but lots of others, too

- Edφ (… of acoustic phi)

- Ed5/3 (… of the classic major sixth)

- Ed9/4 (… of the 3-limit major ninth)

- Ed7/3 (… of the septimal minor tenth)

- Ed5/2 (… of the classic major tenth)

- Ed8/3 (… of the perfect eleventh)

- Ede (… of acoustic e)

- EDT (… of the tritave/twelfth, 3/1)

- most famously approximates the Bohlen–Pierce scale, but lots of others, too

- Ed7/2 (… of the septimal minor fourteenth)

- Ed4 (… of the double octave, 4/1)

- Ed5 (… of the 5th harmonic)

- Ed6 (… of the 6th harmonic)

- Ed7 (… of the 7th harmonic)

- Ed8 (… of the 8th harmonic)

- Ed12 (… of the 12th harmonic)

Equal multiplications

An equal multiplication of a rational interval can also be called an ambitonal sequence (AS). For example, the 25/24 equal-step tuning could also be written AS25/24.

An equal multiplication of an irrational interval can also be called an arithmetic pitch sequence (APS). For example, the 65-cents equal-step tuning could also be written APS65¢.

The union of both is equivalent to the unity division of a target interval. For example, AS25/24 is 1ed25/24, and APS65¢ is 1ed65¢.

List of notable AS

List of notable APS

- APS13.94—13.97¢, tunings for the Delta scale

- APS35.099¢, tuning of Carlos Gamma

- APS63.59—63.82¢, Phoenix tunings

- APS63.833¢, tuning of Carlos Beta

- APS69¢

- APS77.965¢, tuning of Carlos Alpha

- APS86.4¢

- APS88¢

- APS97.5¢

- APS125¢

- Zeta peak index tunings

Edonoi

An equal division of a non-octave interval (EDONOI or edonoi) is a tuning obtained by dividing a non-octave interval in a certain number of equal steps. In a broader sense, any equal-step tuning that is not an integer edo is an edonoi.

The most often used edonoi include the equal-tempering of the Bohlen–Pierce scale (i.e. 13 equal divisions of 3), the Phoenix tuning, tunings of Carlos Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, the 19 equal divisions of 3, the 6 equal divisions of 3/2, the 2 equal divisions of 13/10, and 88cET. For a more extensive gallery, see the #Equal divisions section above.

Some edonoi contain an interval close to 2/1 that might function like a stretched or squashed octave – those edonoi can thus be considered variations on edos.

Other edonoi contain no approximation of an octave or a compound octave (at least, not for a while), and continue generating new tones as they continue upward or downward. Such scales lack a very familiar compositional redundancy, that of octave equivalence – this might necessitate special attention.

See also

- Equal division of the octave

- Families of scales

- Maximal evenness

- Some pages about the same thing as equal-step tuning, but framed differently:

- User:Cmloegcmluin/EPD (ED for short)

- User:Cmloegcmluin/AS

- User:Cmloegcmluin/APS