User:Nick Vuci/TonalityDiamond: Difference between revisions

formatted references |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

The tonality diamond was first formally explained by Max F. Meyer in his 1929 publication ''The Musician's Arithmetic'' using the 7-odd-limit.<ref>[https://archive.org/details/max-f-meyer-the-musicians-arithmetic/page/22/mode/2up Meyer, Max F. "The Musician’s Arithmetic: Drill Problems for an Introduction to the Scientific Study of Musical Composition". ''The University of Missouri Studies''. Vol. 4, no. 1. University of Missouri. January 1, 1929. p. 22.]</ref> | The tonality diamond was first formally explained by Max F. Meyer in his 1929 publication ''The Musician's Arithmetic'' using the 7-odd-limit.<ref>[https://archive.org/details/max-f-meyer-the-musicians-arithmetic/page/22/mode/2up Meyer, Max F. "The Musician’s Arithmetic: Drill Problems for an Introduction to the Scientific Study of Musical Composition". ''The University of Missouri Studies''. Vol. 4, no. 1. University of Missouri. January 1, 1929. p. 22.]</ref> | ||

Harry Partch is the person most associated with the tonality diamond, and | Harry Partch is the person most associated with the tonality diamond, and claimed to have invented it. However, it is likely that he plagarized the idea from Meyer.<ref>[https://www.chrysalis-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/ThePartchHoaxDoctrines.pdf Forster, Cris (2015). ''The Partch Hoax Doctrines''. Self-published.]</ref> | ||

[[Erv Wilson]] in particular was inspired by Partch's use of the tonality diamond and it's extended form. He developed a number of "diamonds" himself,<ref>[https://anaphoria.com/diamond.pdf Wilson, Erv. ''Letters on Diamond Lattices, 1965–1970'' (PDF). Self-published.]</ref> as well as other concepts based on Partch's extended tonality diamond such as "constant structure."<ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/Partchpapers.pdf Wilson, Erv. ''The Partch Papers (collection of documents on Harry Partch’s 11-limit diamond and its extensions), 1964-2002'' (PDF). Self-published.] </ref> | [[Erv Wilson]] in particular was inspired by Partch's use of the tonality diamond and it's extended form. He developed a number of "diamonds" himself,<ref>[https://anaphoria.com/diamond.pdf Wilson, Erv. ''Letters on Diamond Lattices, 1965–1970'' (PDF). Self-published.]</ref> as well as other concepts based on Partch's extended tonality diamond such as "[[constant structure]]."<ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/Partchpapers.pdf Wilson, Erv. ''The Partch Papers (collection of documents on Harry Partch’s 11-limit diamond and its extensions), 1964-2002'' (PDF). Self-published.] </ref> | ||

The first novel xenharmonic temperament — [[George Secor|George Secor's]] later-named "[[Miracle]]" temperament — was made to approximate Partch's 11-limit diamond.<ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/SecorMiracle.pdf Secor, George (1975). “A New Look at the Partch Monophonic Fabric.” ''Xenharmonicon''. Vol. 3]</ref><ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/SecorMiracle.pdf Secor, George. "The Miracle Temperament and Decimal Keyboard". ''Xenharmonikon''. Vol. 18. 2006. pp. 5–15. © 2003.]</ref> | The first novel xenharmonic temperament — [[George Secor|George Secor's]] later-named "[[Miracle]]" temperament — was made to approximate Partch's 11-limit diamond.<ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/SecorMiracle.pdf Secor, George (1975). “A New Look at the Partch Monophonic Fabric.” ''Xenharmonicon''. Vol. 3]</ref><ref>[https://www.anaphoria.com/SecorMiracle.pdf Secor, George. "The Miracle Temperament and Decimal Keyboard". ''Xenharmonikon''. Vol. 18. 2006. pp. 5–15. © 2003.]</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:40, 11 May 2025

WORK-IN-PROGRESS AS OF 10MAY2025

A tonality diamond is a symmetric organization of otonal and utonal chords based around a central note and bounded by an odd-limit. First formalized in the 7-odd-limit by Max F. Meyer in 1929, the idea became central to the music and theories of Harry Partch, who built his tonal system around the 11-odd-limit tonality diamond. Tonality diamonds have been used both conceptually (such as for targets of temperaments) and practically (such as for instrument layouts) in xenharmonics ever since.

Play some tonality diamonds to hear how they sound.

Construction

-

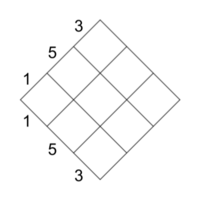

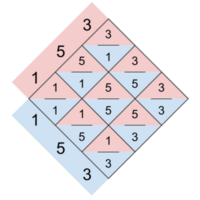

Step 1: Take the numbers of an odd-limit and arrange them along two axes.

-

Step 2: Using one row as the numerator and the other as the denominator, fill in the cells with the ratios they form.

-

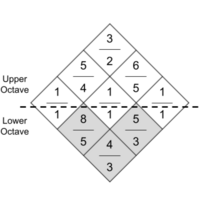

Step 3: Octave-reduce the ratios (ie, make sure the decimal form of each ratio is between 1 and 2; if it is not, double one of the numbers until it is).

-

Optional step: to make the rows play rooted chords, one half of the diamond (not including the middle unison row) must be lowered by an octave (represented by grey cells in image).

Note: the numbers of the odd-limit are generally arranged in one of three ways:

- numerically (ie, 1 3 5 7 9 11) as in Meyer's 7-limit diamond

- by tonal order (ie, 1 9 5 11 3 7) as in Partch's 11-limit diamond

- chordally (ie, 1 5 3 7 9 11) as in the layout for the Diamond Marimba

History

The tonality diamond was first formally explained by Max F. Meyer in his 1929 publication The Musician's Arithmetic using the 7-odd-limit.[1]

Harry Partch is the person most associated with the tonality diamond, and claimed to have invented it. However, it is likely that he plagarized the idea from Meyer.[2]

Erv Wilson in particular was inspired by Partch's use of the tonality diamond and it's extended form. He developed a number of "diamonds" himself,[3] as well as other concepts based on Partch's extended tonality diamond such as "constant structure."[4]

The first novel xenharmonic temperament — George Secor's later-named "Miracle" temperament — was made to approximate Partch's 11-limit diamond.[5][6]

Uses

Instrument layout

The most famous example of the tonality diamond as a practical layout for an instrument is Harry Partch's "Diamond Marimba," which uses the 11-odd-limit tonality diamond exactly. This idea was explored further with Partch's "Quadrangularis Reversum," and by Cris Forster with his 13-odd-limit "Diamond Marimba."

Play with Partch’s Diamond Marimba here.

See also

References

- ↑ Meyer, Max F. "The Musician’s Arithmetic: Drill Problems for an Introduction to the Scientific Study of Musical Composition". The University of Missouri Studies. Vol. 4, no. 1. University of Missouri. January 1, 1929. p. 22.

- ↑ Forster, Cris (2015). The Partch Hoax Doctrines. Self-published.

- ↑ Wilson, Erv. Letters on Diamond Lattices, 1965–1970 (PDF). Self-published.

- ↑ Wilson, Erv. The Partch Papers (collection of documents on Harry Partch’s 11-limit diamond and its extensions), 1964-2002 (PDF). Self-published.

- ↑ Secor, George (1975). “A New Look at the Partch Monophonic Fabric.” Xenharmonicon. Vol. 3

- ↑ Secor, George. "The Miracle Temperament and Decimal Keyboard". Xenharmonikon. Vol. 18. 2006. pp. 5–15. © 2003.